Headcount Planning

TODO:

- Find better vocabulary to distinguish between “leadership team” in your org (that you manage) and “leadership team” that you’re a member of or report to

I once walked into an annual headcount planning session to learn that the other engineering managers in the room had already decided together how they would reallocate the senior members from the infrastructure organization that I supported to the teams that they ran. This was, they assured me, optimal for their roadmaps.

While that was a particularly contentious meeting, headcount planning is hard. It’s an attempt to rationalize priorities across many different teams, each of which works on different sorts of problems. Even when everyone involved has a shared goal of supporting your business, it’s a difficult problem. It can be particularly difficult for infrastructure engineering organizations which often think about their outcomes in unquantified ways: how should you prioritize reducing the risk of a security breach against driving an additional $10 million of revenue?

Meshing infrastructure engineering priorities with a headcount planning process is difficult, but it’s a common challenge for folks working in and leading infrastructure organizations, and there’s a toolkit for navigating the headcount process.

Tools used in this section:

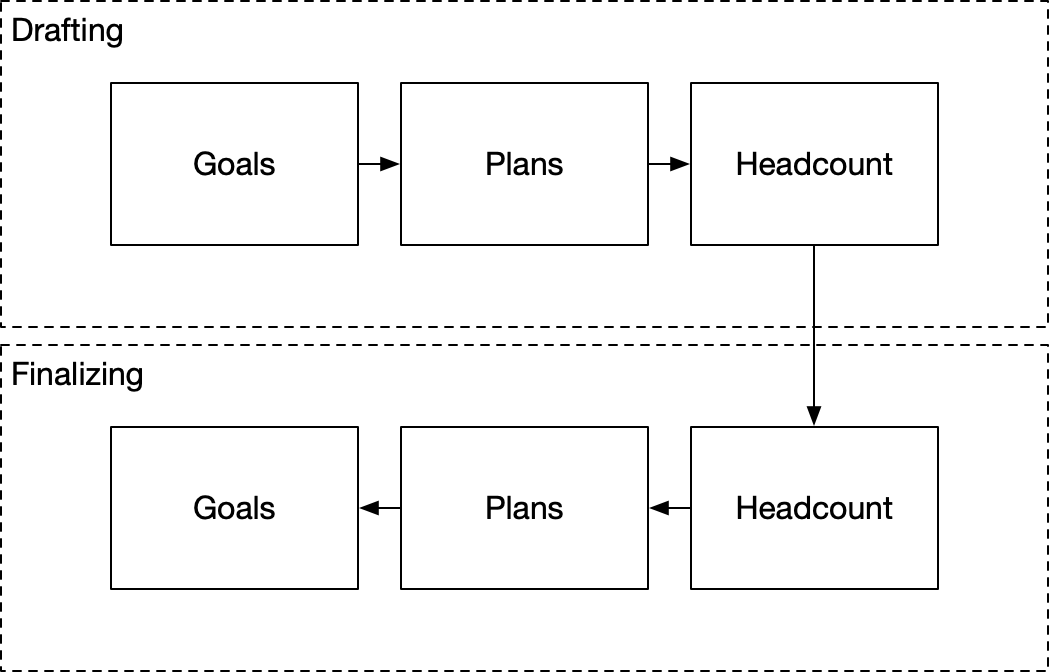

Goals, Plans, and then Headcount

Whenever possible, you should work on headcount after you’ve set organizational goals and translated those goals into a loose plan. Once your headcount plan is finalized, then you’ll need to refine those initial plans and goals with the headcount plan.

Sometimes this ideal sequencing isn’t possible, and that’s ok: there are times to do mediocre work because the alternative is doing abysmal work. However, it’s quite difficult to run an accurate headcount process absent goals and a plan, and you’ll be better off relaxing precision in headcount planning when your goals and planning are ambiguous.

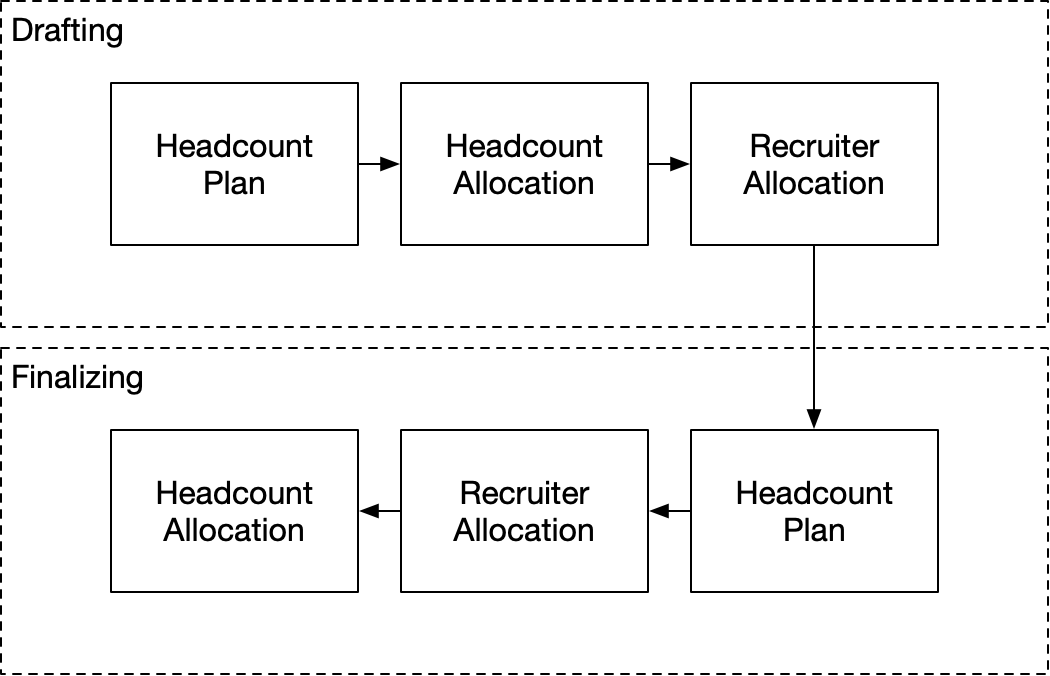

Phases of Headcount Planning

The tidy looking “headcount” box in the planning process hides three distinct phases:

- headcount plan is the company planning and budgeting process (“how many people will we hire this year to hit our company goals and which functions will we hire them in?”)

- headcount allocation is assigning your team’s headcount envelope across roles to be hired (“how do I prioritize these twenty headcount across the infrastructure engineering organization?”)

- recruiter allocation is the mapping of recruiters to both the headcount plan and headcount allocation (“which recruiters will hire these twenty engineering roles?”)

Your headcount planning process almost certainly won’t acknowledge the existence of all of these phases, but it’s important to recognize that they all occur, even if your process pretends otherwise. For example, your headcount planning process may operate as if it’s a top-down process without bottoms-up feedback, but you can be certain that many of your peers are privately providing bottom-ups feedback and advocating for adjustments.

Even if your process acknowledges these three steps, these processes are generally run by different organizations (e.g. executive team, finance team, recruiting team) , and you’ll often find them surprisingly disconnected. If you treat them as a unified process, it’s easy to fall into gaps between the sub-processes (“what do you mean that we’re allocated fifty engineers headcount but won’t have a single recruiter working on engineering hiring until Q3?!”).

Drafting Phase

The headcount process begins with the drafting phase, where your goal is to understand the baseline headcount proposal. This starts with your organizational leader (e.g. VP Engineering) or finance partner (e.g. someone in FP&A) giving you a headcount target to hire against.

Preparing Your Manager for Headcount Planning

A frequent reaction to receiving a headcount plan is to ask, “How was this even established without input from my team?” It can feel quite counterintuitive that your first step in the headcount planning process is to receive a headcount plan. This is, however, generally what happens. To avoid surprises, find a way to remain continuously aligned with your manager on headcount planning.

The two most effective approaches that I’ve encountered are:

- Writing an Organizational Design to align with your organizational leadership on why, when and how the team should grow over time

- Establishing a Hiring Ratio between your team, stakeholder teams, and other growth levers (paying users, etc)

If you’ve aligned with your manager on one of those approaches, then the initial headcount plan you receive should roughly fit with your existing plan. If you haven’t aligned with your manager, then the plan will be whatever your manager makes up, typically driven by inertia (“we grew this team by 30% last year, which was good, so let’s do it again”) or company priorities (“we’re trying to accelerate enterprise sales, so we’re focusing hiring to directly support those initiatives”).

Headcount Plan

This headcount plan will be along the lines of:

- You ended 2021 with twenty engineers

- The budget supports growing to thirty engineers by end of 2022

- There are a set of assumptions about when those hires will happen, for example three hires per quarter in Q1-Q3 and two hires in Q4

- The next planned checkpoints to revise the headcount plan is in early Q3

There may be more details, but they’ll be rough assumptions that you shouldn’t take too seriously. For example, there may be assumptions about how these roles are allocated across teams or roles within your team, but the actual details are going to be up to you to figure out.

Your goal at this point is to understand the headcount proposal. What is the specific proposal? What are the constraints? Where is there flexibility? It is a mistake to raise objections against the initial headcount plan before you understand the constraints that shaped it.

Headcount Allocation

Now that you have the headcount plan, your goal is to translate it into a headcount allocation. The headcount plan is a high-level organizational view of hiring, whereas the headcount allocation is a concrete allocation of that headcount into the specific teams and initiatives that make up your team’s plan and obligations.

You want to come out of headcount allocation with a single document that states:

- Your budget for the next year

- How many additional hires that budget supports

- Which teams those hires will be assigned to

- The relative priority for filling those roles

- What folks should do if they disagree with the plan

You should spend a fair amount of time reviewing this plan in detail with your leadership team and recruiting partners. Your headcount allocation is only useful to the extent that your team is committed to following it.

The best way to determine your headcount allocation is to apply your Organizational Design or Hiring Ratio against the provisional headcount plan. If you said you’ll hire one developer productivity engineer for every ten product engineers and one compute engineer for every twenty engineers, then use those ratios to inform the allocation. If you’ve gotten to this point without either of those documents, take two hours to draft up a proposal and then another hour to discuss it with your leadership team.

Even with a great organizational design or hiring ratio, headcount allocation is not purely a rote process. An overly mechanical approach will run into a few common challenges:

- Inertia-driven planning where you staff based on previous staffing decisions rather than priority

- Overstaffing bad teams that are struggling to close new candidates, retain their existing team, or generally to deliver results. It’s easy to prioritize staffing up these teams, but the impact will be muted until you address the underlying issues

- Starving great teams that are exceeding their goals and consequently don’t “need” more staffing

- Starving new initiatives that don’t fit cleanly into your existing organization

If you run through a hiring allocation process with truly no contention, then either your team has a very high level of trust or you’re dodging all the hard questions that you’d benefit most from addressing.

Recruiter Allocation

Once you’ve completed the headcount allocation, the next step is understanding how the recruiting team is planning to support your hiring efforts. You’re particularly trying to understand if there’s a significant gap between the headcount plan and recruiting support for that plan.

TODO: the wording in list below is verbose and unclear

A typical approach is:

- Identify where alignment happens with recruiting for infrastructure hiring. Start by figuring out what level of your organization is aligning with the recruiters you work with. You’re looking for the place where hiring prioritization happens (“should we hire for the compute team, the SRE team, or the team for product XYZ first?”), and it’s typically the head of engineering at smaller companies (less than ~200 engineers) and sub-leaders beyond that

- Estimate recruiting hiring velocity using the Recruiter Velocity Check. Once you’ve found the level that is aligning with recruiting for your area, then you want to understand the quarterly hiring rates for trained recruiters in that area over the past year. For example, if a recruiting manager with two recruiters is aligned with the head of infrastructure engineering, then how many folks did each recruiter hire within infrastructure engineering in each of the last four quarters? A typical number is going to be four to six hires per quarter per ramped recruiter

- Estimate recruiting ramp up time. Also ask a recruiting manager how long it’s taking new recruiters to ramp up. Many hiring plans assume recruiters are hiring at full capacity from day one, which is a poor assumption. A frequently cited number is three months of ramp time

- Estimate additional hiring to replace attrition. The biggest myth in recruiter allocation is that you only need to hire from your current headcount to the new headcount target, say make ten hires to grow the team from twenty to thirty. In reality you need to make those ten hires and also backfill any attrition that occurs over the year. Attrition numbers vary highly across organizations, but 10% attrition is a reasonable assumption if you have trouble calculating your historical attrition. In this case, it doesn’t matter if this is regretted or non-regretted attrition

- Check recruiter allocation against headcount plan. You now have the pieces of data you need to cross-check the recruiter allocation for your team against the team’s hiring plan. Will you have enough recruiting support to accomplish the hiring plan?

At this point you should understand whether there’s a significant gap between the headcount plan and the recruiter allocation plan. If you believe there is a significant gap, then spend time talking it through with the recruiting team along with whoever is responsible for that recruiting team’s hiring priorities. Your analysis will be helpful in their own efforts to adjust the hiring plan and optimize the hiring process.

Finalizing Phase

Once you’ve completed the drafting phase, the fundamental question to answer is whether things are good enough that you can accept them as is, or whether you need to advocate for changes in the headcount plan.

Some of the smartest folks I’ve worked with have poured a tremendous amount of energy on headcount planning without accomplishing much because they pursue a degree of correctness that headcount planning simply doesn’t support. You should accept the plan as good enough if any of these apply:

- You can solve inaccuracies within your headcount envelope. Headcount planning is a contract between team leaders and the planning process to work within a specific financial plan. The headcount plan doesn’t care if you shift headcount between two teams in your organization as long as the cost impact is relatively neutral

- Things are generally right, even if they’re specifically wrong. Some folks get caught up on headcount plans that have specific errors (“this should be twelve but says eleven”) even though they’re close enough. In practice, headcount plans change all the time and most small errors don’t matter in the long run

- Hiring bandwidth is the real constraint. If you have more headcount than you can hire based on a reasonable recruiting model, then don’t spend a single additional second worrying about the headcount plan. If you’ve already gone deep into optimizing your hiring process then you may want to propose changes to recruiter allocation, but my experience is that you’re almost always better off digging into and debugging your hiring process than advocating for more recruiters

Sometimes, however, you’re going to run into a headcount plan or recruiter allocation that makes your plans difficult, in which case there are a few patterns for negotiating against the initial proposals.

Headcount Planning

If you believe that the headcount plan is so misaligned with your needs that it’s effectively unworkable, then you have a short window to advocate for changes.

Your first instinct may be to write a massive document explaining why your work is important, but hold up a moment. Instead, find someone who has been effective at getting their work staffed, and go talk to them. How did they advocate for their team? What materials did they provide to their manager to show hiring’s impact on their goals and plans? You may come to realize there is an undocumented shadow headcount process that you’ve never realized existed.

After chatting with folks who’ve been effective at getting their headcount asks approved, you’ll usually find one of these things to be true:

- They actually aligned with their manager on an Organizational Design or Hiring Ratio before the headcount process started

- Leadership views a subset of their goals are critical (e.g. product deliverable, SOC2 compliance, security, reliability)

- A revenue driving team has called out this team as essential to their goals (e.g. we can’t close more enterprise b2b deals unless my organization is staffed to complete project X)

- Leadership has a strong relationship with their leadership for whatever reason

In the short-term, your only real option is to do a better job explaining how your team’s plans will impact key or revenue-driving initiatives. Longer term, this is a heads up that you could be doing a better job of connecting your organization’s goals to things your organization values.

Recruiter Allocation

Once your headcount plan is finalized, regroup with the recruiting team you partner with and discuss any needed changes. Even if your model suggests you need more recruiters, at this point you’ve made your case and should focus on how you can partner most effectively to take good advantage of the support you will have.

Headcount Allocation

At this point, you have the final headcount plan and it’s time to refresh your hiring allocation to reflect any changes that have been made. This should be a lightweight rerunning of the process you used for the initial headcount allocation and then communicating the updated plan to your team.

What’s next?

At this point, you’re done with the headcount process, and you can move on to finalizing your goals and plans based on the final numbers.

Sometimes folks will get frustrated with where the headcount allocation ends up, which is natural given the number of priorities being balanced against each other. What I’ve learned over time is that these things get revised sooner than later: if someone is upset, then work with them on putting together the data for a better rationale when you start the next headcount process.